The importance of real things in a digital age

How an encounter with Charles Dickens and Winnie the Pooh gave me hope for the future

I admit it, we were there because of Ghostbusters.

I wanted to see the lions outside the New York Public Library. I wanted to see the steps that Peter, Ray and Egon ran down after seeing the library ghost. A place I knew so well from my favourite film and yet had never sought out in all my visits to New York.

And there they were, resplendent in their festive finery.

It never even dawned on me that we could go inside the library until Clare pointed out there was an exhibit celebrating 100 years of The New Yorker. So inside we went and almost immediately stumbled upon a small glass cabinet containing unbelievable treasures.

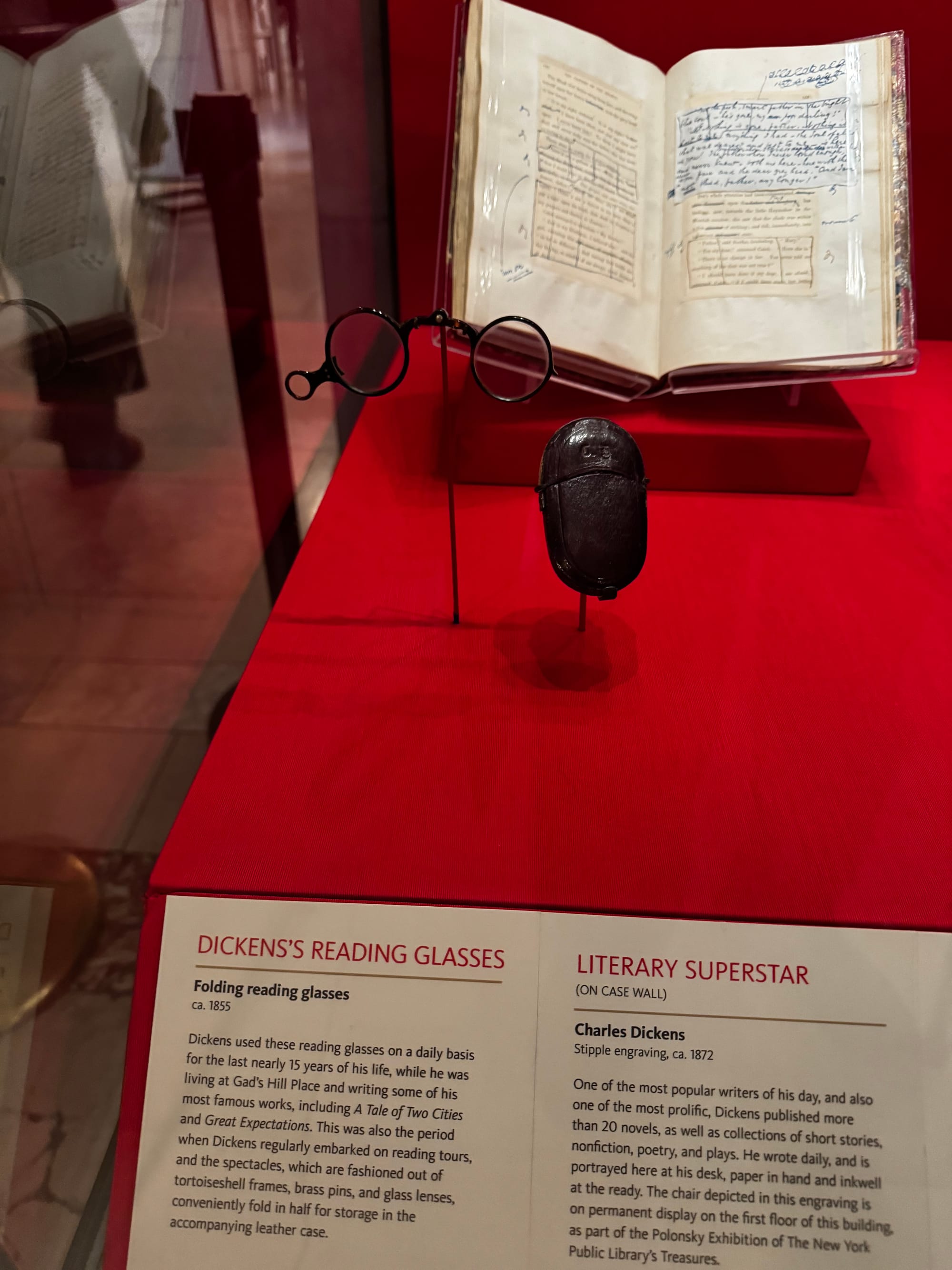

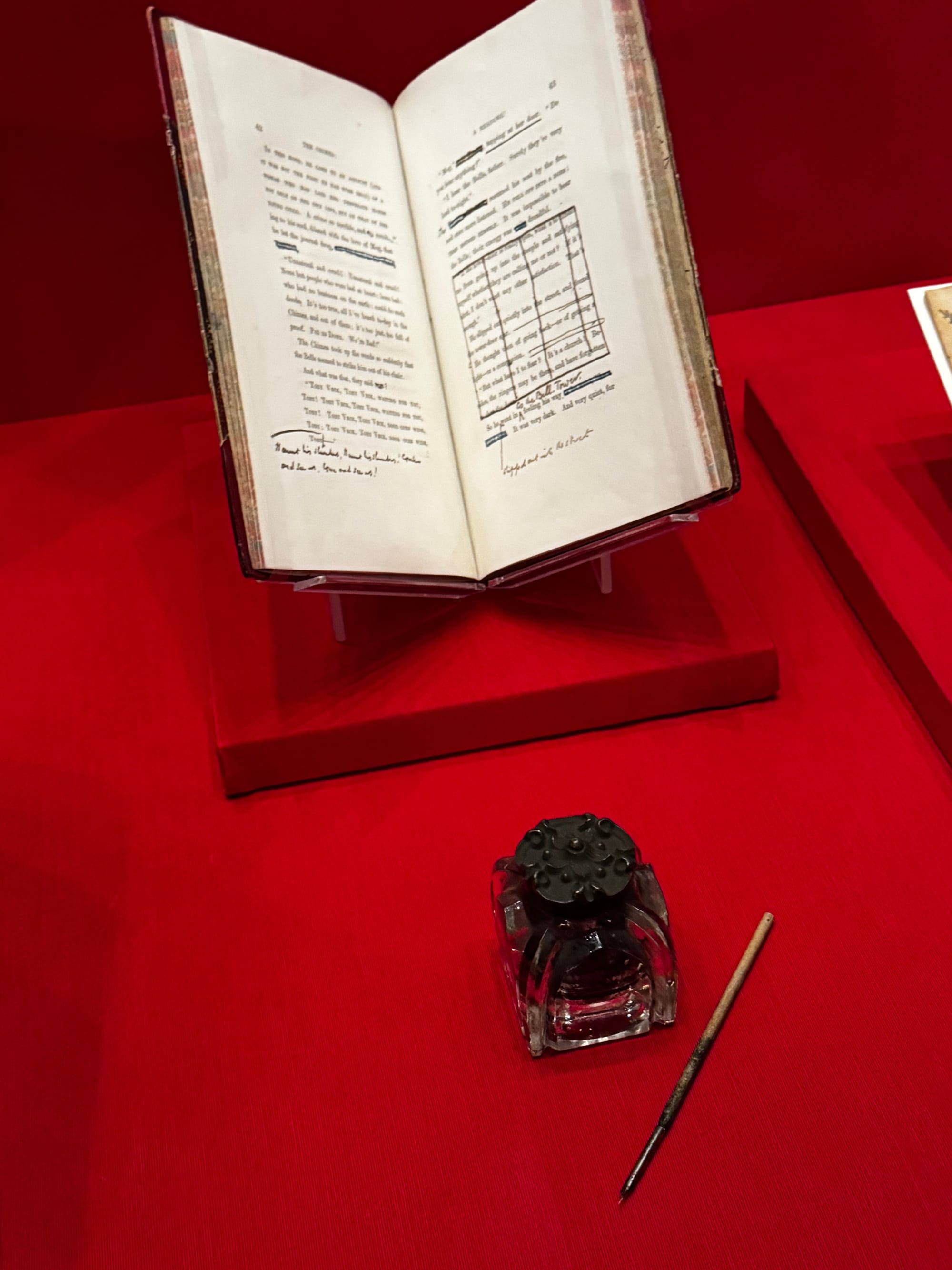

There in front of us were a pair of spectacles that had belonged to Charles Dickens alongside his pot of ink. Most exciting of all, for me at least, was Dickens’ copy of A Christmas Carol he used on his tours of America, complete with annotations in his own hand.

I couldn’t believe it. As Ghostbusters is my favourite film, the story of Ebenezer Scrooge is my favourite book and here I was standing, staring at the author’s handwriting in awe.

That’s when Clare came up excitedly and told me that Winnie the Pooh was downstairs. The real Winnie the Pooh as owned by the real Christopher Robin. And so we set off to find a corner of the Hundred Acre Wood in New York City and were rewarded with the sight of another glass cabinet, not only containing the silly old bear, but his friends too (all except Roo who heartbreakingly was lost by Christopher in a cherry orchard.)

What unexpected joy on a cold, December morning — little memories we will never forget and an important reminder in these days of AI and digital items that there is something magical about real things. Why was I so fascinated by a pair of old spectacles? Because they used to sit on the nose of one of the greatest writers of all time. Why did we get misty-eyed standing in front of a set of old toys? Because they were the toys that inspired stories that have found a place in our hearts. Even those proud lions on the library steps. They were a tangible link to a film I’ve loved since I was ten.

It’s why we queue for authors to sign our books, why collectors spend a small fortune for a costume worn by a much-loved actor. These things are proof of life. Proof of authenticity, a connection between artist and audience. In his book Craftland: A Journey Through Britain’s Lost Arts & Vanishing Trades, writer James Fox says that whenever you encounter a hand-crafted object “you are meeting something that is by definition unique, with its own fingerprints of quirks and imperfections”, something that “bears the indexical residue of a particular moment in time, when a human being put something into the world that didn’t exist before and couldn’t exist anywhere else.”

AI is going to change the world. That genie is out of the bottle. And the jury is out about whether that is going to be a good or a bad thing. But the flutter of excitement I felt examining a man’s 170-year-old handwriting or gazing at much-cuddled toys gives me hope that whatever machines output, we will always look for authentic connection to the art we love, the proof of human life in a landscape filled with pixels and artifice.

Share this post

The Cavletter is the newsletter and blog of NYT bestselling author, comic creator and screenwriter Cavan Scott — sharing thoughts on the creative life, bookish adventures, and recommendations for things to read, watch and listen.

Enjoying it? Forward it to a friend — so they can subscribe here.